Open Access, Peer-reviewed

eISSN 2093-9752

Open Access, Peer-reviewed

eISSN 2093-9752

Ji-Hoon Cho

Sang-Won Seo

Namwoong Kim

http://dx.doi.org/10.5103/KJAB.2025.35.4.289 Epub 2025 December 08

Abstract

Objective: The purpose of this study was to objectively identify common landing errors in female basketball players by integrating the Landing Error Scoring System (LESS) with OpenCap.

Method: Eleven collegiate female basketball players were recruited to perform a LESS jump landing task from a 30 cm high box. Landing mechanics were recorded using two iOS devices via OpenCap. A modified full-body musculoskeletal model was used in conjunction with OpenSim's inverse kinematics to objectively quantify landing mechanics, including multi-planar knee joint motion.

Results: The mean LESS was 5.64 ± 0.77, placing the participants in the moderate category of landing mechanics. The most frequently observed error was knee valgus displacement (LESS item 15), present in all participants. Joint displacement (LESS item 16) and knee valgus angle at initial contact (LESS item 5) were also prevalent, observed in 90.91% and 81.82% of participants, respectively. Based on LESS score distributions, 55% of participants categorized as having moderate landing mechanics, 27% as good, 9% as poor, and 9% as excellent.

Conclusion: The results of our study indicate that targeted interventions may be necessary to reduce Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) injury risk among female basketball players. Integrating LESS scores with OpenCap provides a practical and accessible approach to identifying key biomechanical risk factors associated with ACL injury.

Keywords

Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) injury Landing Error Scoring System (LESS) OpenCap Female basketball players

Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury is prevalent among young athletes and is considered one of the most debilitating injuries, especially in athletes participating in high-impact sports such as basketball (Agel et al., 2007; Deitch, Starkey, Walters & Moseley, 2006; Leppanen et al., 2017; Munro, Herrington & Comfort, 2012; Taylor et al., 2017). The economic impact of ACL injuries is significant, with the direct costs of surgical procedures and rehabilitation ranging from $17,000 to $25,000 per injury (Hewett, Lindenfeld, Riccobene & Noyes, 1999; Loes, Dahlstedt & Thomée, 2000). Considering the potential losses, including loss of scholarships, professional opportunities, as well as an increased risk of osteoarthritis, the long-term costs could impose a significant economic burden on individuals and society. To mitigate these burdens, cost-effective and field-deployable screening tools that can provide objective data are needed, particularly among high-risk populations. Notably, female athletes who participate in pivoting and jumping sports such as basketball have a four to sixfold greater incidence of ACL injury compared to their male counterparts (Agel et al., 2007; Arendt & Dick, 1995; Deitch et al., 2006; Malone, 1992; Munro et al., 2012; Myklebust et al., 2003). Therefore, greater attention should be directed toward identifying sex-specific risk factors and incorporating them into clinical decision-making processes.

Functional tests and other assessment tools have been widely used to screen for injury risk and to guide individualized interventions (Brown, Ko, Rosen & Hsieh, 2015; de la Motte, Arnold & Ross, 2015; Hertel, Braham, Hale & Olmsted-Kramer, 2006; Rosen, Needle & Ko, 2019; Zwolski, Schmitt, Thomas, Hewett & Paterno, 2016). Among these, the Landing Error Scoring System (LESS) is frequently employed to identify move- ment patterns associated with ACL and other lower extremity injuries (Beese, Joy, Switzler & Hicks-Little, 2015; Bell, Smith, Pennuto, Stiffler & Olson, 2014; Hanzlikova, Athens & Hebert-Losier, 2020, 2021; Morooka et al., 2023; Padua et al., 2009). The LESS is relatively quick and inexpensive to administer, however, its scoring process requires trained raters to visually inspect video recordings or live performance, which may introduce variability and reduce accuracy (Padua et al., 2009).

To overcome some of these limitations of observational assessments, various studies have used three-dimensional (3D) motion capture systems to collect more precise kinematic data. However, the application of such systems is often restricted by spatial constraints and high costs. A markerless motion capture system, OpenCap, has offered a viable alternative. OpenCap integrates deep learning algorithms with cloud-based muscu- loskeletal modeling to generate 3D kinematics from videos recorded by as few as two smartphone cameras (Uhlrich et al., 2023; Verheul, Robinson & Burton, 2024). Prior validation studies reported that OpenCap can estimate joint angles and moments with mean absolute errors of approximately 4-5° and 1.2% body weight×height, respectively, achieving accur- acy comparable to marker-based 3D motion capture systems (Turner, Chaaban & Padua, 2024; Uhlrich et al., 2023). These findings indicate that OpenCap may serve as a practical tool for conducting field-based assessments. Although OpenCap shows promise, it has not yet been systematically integrated with established clinical assessment tools such as the LESS, and the use of the integrated approach among female basketball players remains limited.

Therefore, the purpose of this study was to objectively identify common landing errors among female basketball players by integrating the LESS with OpenCap. This combined approach is expected to offer a more accessible means of assessing ACL injury risk and may contribute to the develop- ment of practical, field-based screening protocols that help reduce the personal and economic burdens associated with such injuries.

1. Participants

Eleven collegiate female basketball players participated in this study (n = 11, age = 21.27±1.10 yrs, height = 166.27±8.15 cm, mass = 59.25±8.37 kg). Participants were included if they were free from lower extremity injury and had no history of lower extremity injury within the six months prior to data collection. All participants read and signed an approved in- formed consent document prior to data collection.

2. Experimental procedure

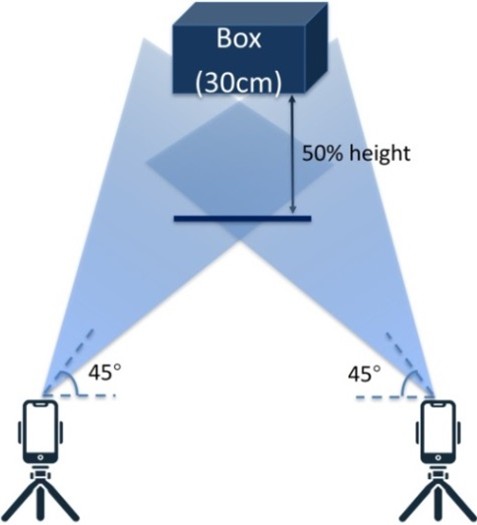

The jump landing task was based on the methodology out- lined by Padua et al. (Padua et al., 2009). Participants jumped from a 30 cm high box, landing on both feet at a target set at 50% of each participant’s height from the box. Following the setup described in Uhlrich et al. (Uhlrich et al., 2023), two iOS devices were mounted on tripods at a height of 1.2 meters and positioned around the participants (Figure 1). Three-dimensional kinematic data were collected using the cloud-based OpenCap platform.

3. Musculoskeletal modeling and analysis

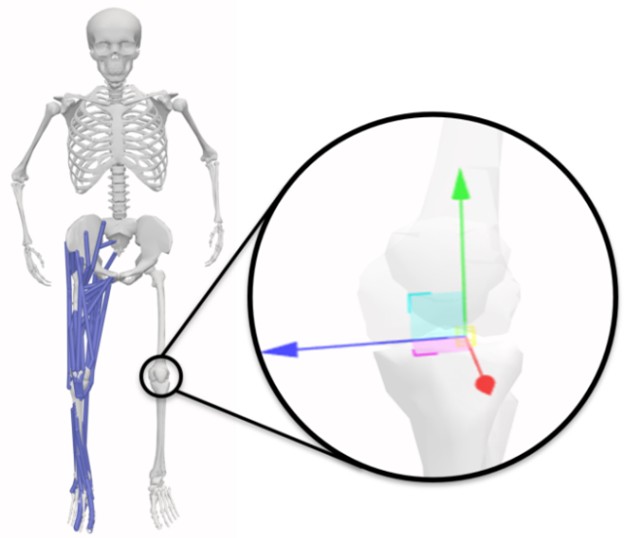

Video recordings from the two iOS devices were uploaded and processed in OpenCap to estimate joint kinematics using a full-body musculoskeletal model (Lai, Arnold & Wakeling, 2017; Rajagopal et al., 2016). Following data collection, Open- Cap files for each LESS trial were downloaded for subsequent offline analysis. The offline analysis involved two primary pro- cedures. Initially, the musculoskeletal model's knee joint was modified by adding two additional degrees of freedom. This modification enabled a more precise representation of knee joint motion in the frontal and transverse planes, which is particularly important for LESS scoring (Figure 2). Second, joint angles from the recorded LESS trials were calculated using OpenSim's inverse kinematics tool.

4. LESS scoring

For LESS scoring, angles for knee flexion, hip flexion, trunk flexion, plantar flexion, knee valgus, and lateral trunk flexion were calculated using OpenSim's inverse kinematics tool. These measurements were then used to score LESS items 1 through 7 at initial contact. Stance width, relevant to LESS items 8 and 9, was calculated using the acromion and lateral malleolus markers on the scaled musculoskeletal model, which were then used to classify the stance as either wide or narrow. Foot positioning for LESS items 10 and 11, indicating external and internal rotation, was determined from the subtalar angle. The symmetry of initial foot contact (LESS item 12) was evaluated by measuring the vertical height difference between toe markers, with a difference of less than 4 cm considered sym- metrical. The velocity upon landing from a height of 30 cm was calculated using the free fall formula, yielding 2.43 m/s. Given the data collection frequency of 60 Hz, the potential measurement variability was determined to be 4.03 cm. There- fore, a 4 cm cutoff was chosen to accommodate this potential variability.

The displacement of knee, hip, and trunk flexion angles from initial contact to the point of maximum knee flexion (LESS items 13-15) was also calculated using results from OpenSim's inverse kinematics tool. The criteria for determining landing softness (LESS item 16) were adapted from a previous study (Devita & Skelly, 1992), with a knee angle of less than 77° classified as a stiff landing, between 77° and 117° classified as an average landing, and greater than 117° classified as a soft landing.

For LESS item 17, we adopted criteria tailored to bilateral jump landings, informed by a study (Kristianslund, Faul, Bahr, Myklebust & Krosshaug, 2014) on knee valgus, lateral trunk flexion, and trunk rotation during side cutting in female volley- ball athletes, however we used more conservative thresholds given the nature of the movement under investigation:

i. Excellent (score 0): All angles (knee valgus, torso lateral flexion, and torso rotation) were less than 5°.

ii. Average (score 1): At least one angle ranged between 5° and 10°.

iii. Poor (score 2): At least one angle exceeded 10°

It is important to acknowledge that the LESS scoring criteria differ depending on the specific item. For certain items, an error is recorded when the expected movement criterion is met (Yes), whereas for others, an error is assigned when the criterion is not met (No).

1. LESS score

LESS scores are shown in Table 1. The overall mean LESS score for the participants was 5.64±0.77. LESS item 15 (knee valgus displacement) had the highest mean score (1.00±0.00). LESS item 5 (knee valgus angle at initial contact) had a mean score of 0.82±0.39. LESS item 12 (knee flexion displacement: >45°) showed a mean score of 0.73±0.45. LESS items 4 (ankle plantar flexion at initial contact) and 13 each scored 0.18±0.39. LESS items 7 and 8 each scored 0.09±0.29. For items with a scoring range of 0 to 2, LESS item 16 (joint displacement) had a mean score of 1.18±0.39, and LESS item 17 (overall impression) had a mean score of 1.27±0.75.

|

LESS item |

Mean (SD) of LESS score |

|

1.

Knee flexion angle at initial contact: greater than 30° Yes

= 0, No = 1 |

0.09

(0.29) |

|

2.

Hip flexion angle at initial contact: hips are flexed Yes

= 0, No = 1 |

0.00

(0.00) |

|

3.

Trunk flexion angle at initial contact: trunk in front of hips Yes

= 0, No = 1 |

0.00

(0.00) |

|

4.

Ankle plantar flexion at initial contact: greater than 0° Yes

= 0, No = 1 |

0.18

(0.39) |

|

5.

Knee valgus angle at initial contact: greater than 0° Yes

= 1, No = 0 |

0.82

(0.39) |

|

6.

Lateral trunk flexion at initial contact Yes

= 1, No = 0 |

0.00

(0.00) |

|

7.

Stance width-wide: > shoulder width Yes

= 1, No = 0 |

0.09

(0.29) |

|

8.

Stance width-narrow: < shoulder width Yes

= 1, No = 0 |

0.09

(0.29) |

|

9.

Foot position: external rotation: > 30° Yes

= 1, No = 0 |

0.00

(0.00) |

|

10.

Foot position: internal rotation: > 30° Yes

= 1, No = 0 |

0.00

(0.00) |

|

11.

Symmetric initial foot contact: less than 4 cm difference Yes

= 0, No = 1 |

0.00

(0.00) |

|

12.

Knee flexion displacement: > 45° Yes

= 0, No = 1 |

0.73

(0.45) |

|

13.

Hip flexion displacement: greater than at initial contact Yes

= 0, No = 1 |

0.18

(0.39) |

|

14.

Trunk flexion displacement: greater than at initial contact Yes

= 0, No = 1 |

0.00

(0.00) |

|

15.

Knee valgus displacement: peak knee valgus angle greater than initial contact Yes

= 1, No = 0 |

1.00

(0.00) |

|

16.

Joint displacement Soft

= 0, Average = 1, Stiff = 2 |

1.18

(0.39) |

|

17.

Overall impression Excellent

= 0, Average = 1, Poor = 2 |

1.27

(0.75) |

|

Group Mean |

5.64 (0.77) |

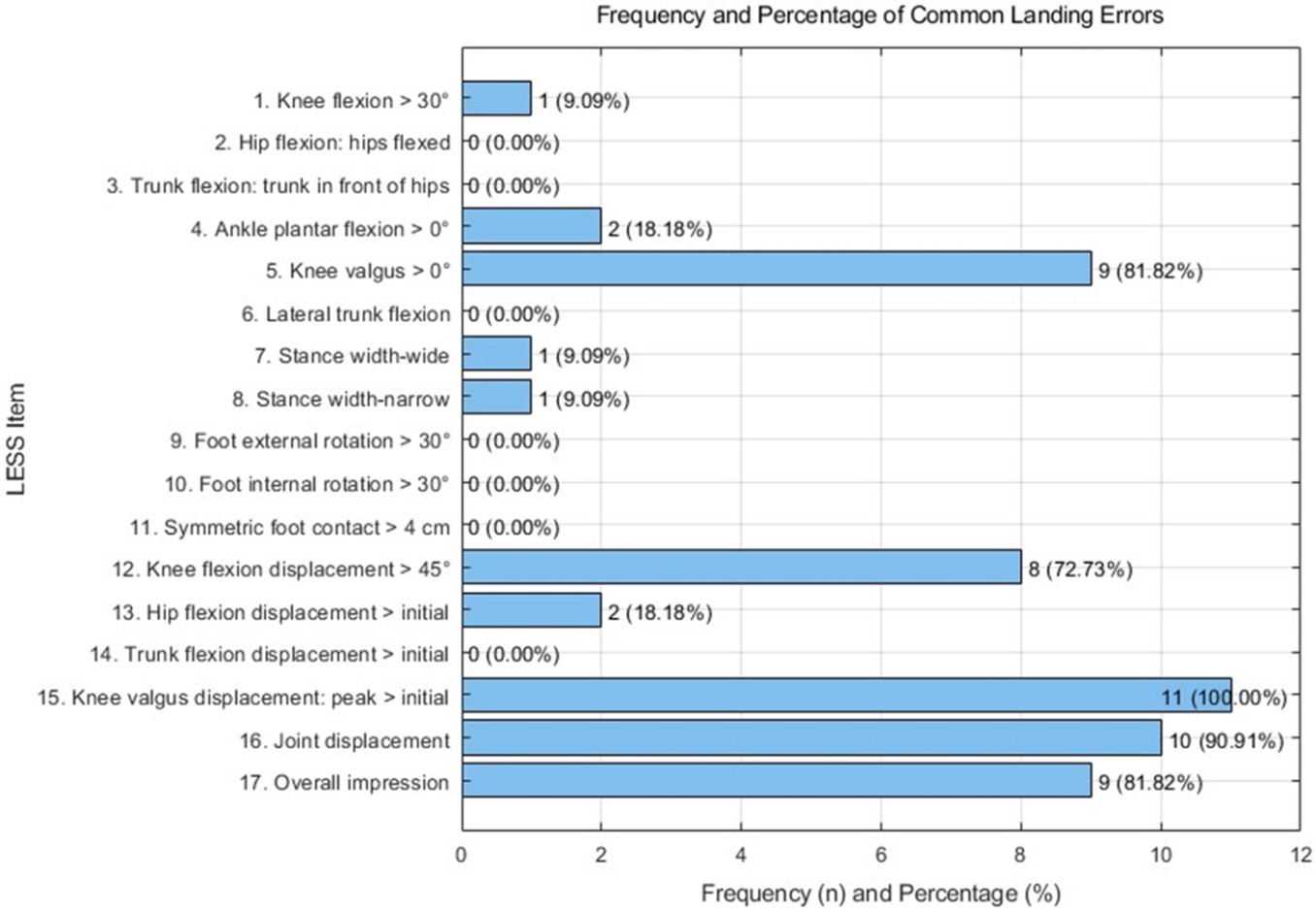

2. Frequency and percentage of common landing errors

Frequency and percentage of common landing errors are shown in Figure 3. The most frequent landing error was LESS item 15 (knee valgus displacement), observed in all partici- pants (100%). LESS item 16 (joint displacement) occurred in 10 participants (90.91%), and LESS item 17 (overall impression indicating poor to average landing mechanics) appeared in 9 participants (81.82%). LESS item 5 (knee valgus at initial contact) was noted in 9 participants (81.82%).

LESS item 12 (knee flexion displacement >45°) was observed in 8 participants (72.73%). LESS items 4 (ankle plantar flexion at initial contact) and 13 (hip flexion displacement) each occurred in 2 participants (18.18%). LESS items 1 (knee flexion angle at initial contact >30°), 7 (stance width-wide), and 8 (stance width-narrow) were each seen in 1 participant (9.09%).

3. Distribution of LESS scores

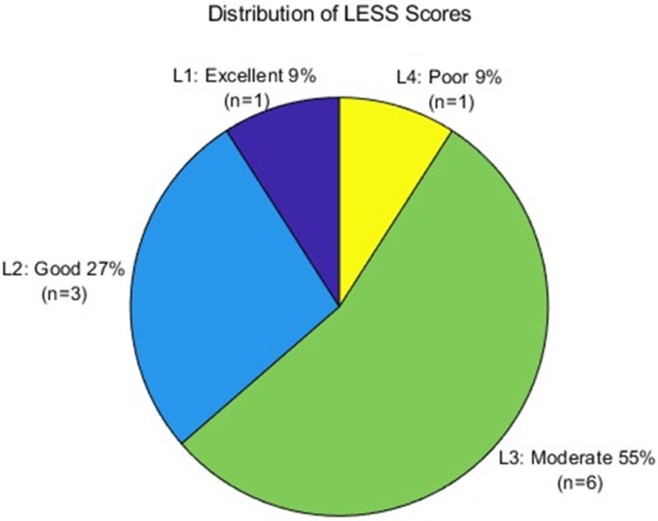

Participants were classified into four categories based on their LESS scores: excellent (≤4), good (>4 to ≤5), moderate (>5 to ≤6), and poor (>6) (Padua et al., 2009). The distribution was as follows: moderate (55%, n = 6), good (27%, n = 3), excellent (9%, n = 1), and poor (9%, n = 1) (Figure 4).

The purpose of this study was to improve injury risk assess- ment in female basketball players by integrating the LESS with OpenCap. This combined approach not only has the potential to provide more accurate and objective evaluations of landing mechanics associated with ACL injury risk but also demon- strates how the LESS and OpenCap can be applied to identify landing errors related to ACL and other lower extremity injuries.

The mean LESS score observed in this study (5.64±0.77) was similar to that reported in a previous study (6.00±2.13) involving female basketball players (Lisman, Wilder, Berenbach, Jiao & Hansberger, 2021). These results suggest that female basketball players may have a moderate level of landing errors. However, it is important to acknowledge that the prior study used a modified LESS rubric which included 22 items but excluded two subjective items, resulting in a maximum score of 21. In contrast, this study used the original 17 item rubric with a maximum score of 19. This methodological difference may partially account for variations in total LESS scores and should be considered when making comparisons across studies.

Knee valgus displacement (LESS item 15) was the most frequent landing error, observed in all participants. Previous studies have identified dynamic knee valgus as a significant risk factor for ACL injury (Deitch et al., 2006; Hewett et al., 2005; Hewett, Myer, Ford, Paterno & Quatman, 2016; Quatman et al., 2014). The second most common error was joint dis- placement (LESS item 16), observed in 90.91% of participants. This result indicates that the participants did not demonstrate sufficient flexion at the hip, knee, and ankle joints during landing. Such stiff landing mechanics may elevate impact forces, thereby increasing the load transferred to passive structures, including ligaments, cartilage, and joint capsules (Hewett et al., 2016). When combined with dynamic knee valgus, this stiff landing strategy may substantially increase the risk of ACL injury (Larwa, Stoy, Chafetz, Boniello & Franklin, 2021; Tamura et al., 2017). The overall impression scores (LESS item 17) indicated that 81.82% of the participants exhibited average to poor landing mechanics. Collectively, our findings indicate that dynamic knee valgus, insufficient joint displacement, and excessive frontal plane movement should be prioritized as key targets in ACL injury prevention for female basketball players (Hewett, Ford & Myer, 2006; Hewett et al., 2005; Hewett et al., 2016). It is important to develop clinical assessment tools that can quantify these movement deficits accurately and reliably (Myers et al., 2011). Therefore, we developed an integrated approach that identifies movement patterns associated with ACL injury. This combined approach supports continuous moni- toring and may allow early detection of recurrent movement deficits that can be modified through targeted interventions. In practice, this simple setup allows practitioners to screen an entire team on the court using only two smartphones and the LESS checklist. Following screening, athletes demonstrating sub- optimal landing mechanics can receive immediate corrective feedback.

Approximately two-thirds of the participants in this study were classified within the moderate to poor landing mechanics category. Similarly, previous research has found that both injured and noninjured female basketball players had average LESS scores of 7 and 8, which fall within the poor landing cate- gory (Siupsinskas, Garbenyte-Apolinskiene, Salatkaite, Gudas & Trumpickas, 2019). Although our participants had no recent history of injury, their moderate-to-poor LESS scores indicate that they may still have underlying movement patterns that could increase their risk of ACL injury. Therefore, improving landing mechanics may be an important component in re- ducing the risk of lower extremity injuries in this population.

There were several limitations in this study. First, our sample included only female basketball players. While aligned with our aims, this focus may limit generalizability. Future studies should include a broader range of participants to verify that the bene- fits of this combined approach hold across sexes and sports. Second, although OpenCap has demonstrated good validity for measuring lower limb kinematics during jump landing tasks, minor measurement errors or misestimations can occur especially if video quality or camera positioning is suboptimal. We mitigated this by following established OpenCap setup protocols, but subtle inaccuracies in joint angle estimation cannot be entirely ruled out. Third, the LESS does not explicitly specify precise thresholds to distinguish between "soft," "aver- age," and "stiff" for LESS item 16 (joint displacement), and "large," "average," and "poor" for LESS item 17 (overall im- pression). Although we followed the criteria used in previous studies, the lack of universal thresholds for these items may affect scoring consistency. Finally, we assessed biomechanical risk factors at a single time point and did not track whether basketball players who scored poorly, eventually sustained ACL injuries. Prospective longitudinal studies are needed to determine whether interventions informed by the LESS and OpenCap ultimately reduce ACL injury risk.

Despite these limitations, this study presents several distinct strengths. First, we utilized musculoskeletal models to calculate joint kinematics more accurately. Specifically, we added two degrees of freedom to the knee joint to describe frontal and transverse plane motion, which is closely linked to ACL injury risk. Second, we aimed to enhance the objectivity of the LESS by quantifying items 16 and 17, which are typically scored subjectively. The use of measurable criteria for these items may help improve consistency in the assessment process across raters. Future work should refine and standardize these criteria to support more reliable LESS assessment.

This study integrated the LESS with OpenCap to objectively evaluate movement patterns associated with ACL injury risk in female basketball players. We observed dynamic knee valgus, insufficient joint displacement, and excessive frontal plane movement, all of which have been associated with an in- creased risk of ACL injury. Targeted interventions appear to be necessary to address the identified deficits and reduce ACL injury risk in female basketball players. Future research is needed to evaluate whether the integrated approach and the targeted interventions it informs improve landing mechanics and reduce ACL injury risk. A larger and more diverse sample, including athletes from diverse sports, would also enhance the generalizability of these results and provide insight into sport-specific landing mechanics related to ACL injury risk.

References

1. Agel, J., Olson, D. E., Dick, R., Arendt, E. A., Marshall, S. W. & Sikka, R. S. (2007). Descriptive epidemiology of collegiate women's basketball injuries: National Collegiate Athletic Association Injury Surveillance System, 1988-1989 through 2003-2004. Journal of Athletic Training, 42(2), 202-210.

Google Scholar

2. Arendt, E. & Dick, R. (1995). Knee injury patterns among men and women in collegiate basketball and soccer: NCAA data and review of literature. The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 23(6), 694-701.

Google Scholar

3. Beese, M. E., Joy, E., Switzler, C. L. & Hicks-Little, C. A. (2015). Landing error scoring system differences between single-sport and multi-sport female high school-aged athletes. Journal of Athletic Training, 50(8), 806-811.

Google Scholar

4. Bell, D. R., Smith, M. D., Pennuto, A. P., Stiffler, M. R. & Olson, M. E. (2014). Jump-landing mechanics after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: A landing error scoring system study. Journal of Athletic Training, 49(4), 435-441.

Google Scholar

5. Brown, C. N., Ko, J., Rosen, A. B. & Hsieh, K. (2015). Individuals with both perceived ankle instability and mechanical laxity demonstrate dynamic postural stability deficits. Clinical Biomechanics, 30(10), 1170-1174.

Google Scholar

6. de la Motte, S., Arnold, B. L. & Ross, S. E. (2015). Trunk-rotation differences at maximal reach of the star excursion balance test in participants with chronic ankle instability. Journal of Athletic Training, 50(4), 358-365.

Google Scholar

7. Deitch, J. R., Starkey, C., Walters, S. L. & Moseley, J. B. (2006). Injury risk in professional basketball players: A comparison of Women's National Basketball Association and National Basketball Association athletes. American Journal of Sports Medicine, 34(7), 1077-1083.

Google Scholar

8. Devita, P. & Skelly, W. A. (1992). Effect of landing stiffness on joint kinetics and energetics in the lower extremity. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 24(1), 108-115.

Google Scholar

9. Hanzlikova, I., Athens, J. & Hebert-Losier, K. (2020). Clinical implications of landing error scoring system calculation methods. Physical Therapy in Sport, 44, 61-66.

Google Scholar

10. Hanzlikova, I., Athens, J. & Hebert-Losier, K. (2021). Factors influencing the landing error scoring system: Systematic review with meta-analysis. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 24(3), 269-280.

11. Hertel, J., Braham, R. A., Hale, S. A. & Olmsted-Kramer, L. C. (2006). Simplifying the star excursion balance test: Analyses of subjects with and without chronic ankle instability. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 36(3), 131-137.

Google Scholar

12. Hewett, T. E., Ford, K. R. & Myer, G. D. (2006). Anterior cruciate ligament injuries in female athletes: Part 2, a meta-analysis of neuromuscular interventions aimed at injury prevention. The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 34(3), 490-498.

Google Scholar

13. Hewett, T. E., Lindenfeld, T. N., Riccobene, J. V. & Noyes, F. R. (1999). The effect of neuromuscular training on the in- cidence of knee injury in female athletes. The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 27(6), 699-706.

Google Scholar

14. Hewett, T. E., Myer, G. D., Ford, K. R., Heidt Jr, R. S., Colosimo, A. J., McLean, S. G., Van den Bogert, A. J., Paterno, M. V. & Succop, P. (2005). Biomechanical measures of neuro- muscular control and valgus loading of the knee predict anterior cruciate ligament injury risk in female athletes: a prospective study. The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 33(4), 492-501.

Google Scholar

15. Hewett, T. E., Myer, G. D., Ford, K. R., Paterno, M. V. & Quatman, C. E. (2016). Mechanisms, prediction, and prevention of ACL injuries: Cut risk with three sharpened and validated tools. The Journal of Orthopaedic Research, 34(11), 1843-1855.

Google Scholar

16. Kristianslund, E., Faul, O., Bahr, R., Myklebust, G. & Krosshaug, T. (2014). Sidestep cutting technique and knee abduction loading: Implications for ACL prevention exercises. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 48(9), 779-783.

Google Scholar

17. Lai, A. K., Arnold, A. S. & Wakeling, J. M. (2017). Why are antagonist muscles co-activated in my simulation? A musculoskeletal model for analysing human locomotor tasks. Annals of Biomedical Engineering, 45(12), 2762-2774.

Google Scholar

18. Larwa, J., Stoy, C., Chafetz, R. S., Boniello, M. & Franklin, C. (2021). Stiff landings, core stability, and dynamic knee valgus: A systematic review on documented anterior cruciate ligament ruptures in male and female athletes. International Journal of Environmental Research, 18(7).

Google Scholar

19. Leppanen, M., Pasanen, K., Kujala, U. M., Vasankari, T., Kannus, P., Ayramo, S., Krosshaug, T., Bahr, R., Avela, J., Perttunen, J. & Parkkari, J. (2017). Stiff landings are associated with increased ACL injury risk in young female basketball and floorball players. American Journal of Sports Medicine, 45(2), 386-393.

20. Lisman, P., Wilder, J. N., Berenbach, J., Jiao, E. & Hansberger, B. (2021). The relationship between landing error scoring system performance and injury in female collegiate athletes. International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy, 16(6), 1415-1425.

Google Scholar

21. Loes, M. D., Dahlstedt, L. J. & Thomée, R. (2000). A 7-year study on risks and costs of knee injuries in male and female youth participants in 12 sports. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 10(2), 90-97.

Google Scholar

22. Malone, T. (1992). Relationship of gender in anterior cruciate ligament injuries of NCAA division I basketball players. Journal of the Southern Orthopaedic Association, 2, 36-39.

Google Scholar

23. Morooka, T., Yoshiya, S., Tsukagoshi, R., Kawaguchi, K., Fujioka, H., Onishi, S., Nakayama, H., Nagura, T., Tachibana, T. & Iseki, T. (2023). Evaluation of the anterior cruciate liga- ment injury risk during a jump-landing task using 3-dimensional kinematic analysis versus the landing error scoring system. Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine, 11(11), 23259671231211244. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 23259671231211244

Google Scholar

24. Munro, A., Herrington, L. & Comfort, P. (2012). Comparison of landing knee valgus angle between female basketball and football athletes: Possible implications for anterior cruciate ligament and patellofemoral joint injury rates. Physical Therapy in Sport, 13(4), 259-264. https://doi.org/10.1016/ j.ptsp.2012.01.005

Google Scholar

25. Myers, C. A., Torry, M. R., Peterson, D. S., Shelburne, K. B., Giphart, J. E., Krong, J. P., Woo, S. L. & Steadman, J. R. (2011). Measurements of tibiofemoral kinematics during soft and stiff drop landings using biplane fluoroscopy. American Journal of Sports Medicine, 39(8), 1714-1722. https://doi.org/10.1177/0363546511404922

Google Scholar

26. Myklebust, G., Engebretsen, L., Brækken, I. H., Skjølberg, A., Olsen, O. E. & Bahr, R. (2003). Prevention of anterior cruciate ligament injuries in female team handball players: A prospective intervention study over three seasons. Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine, 13(2), 71-78.

Google Scholar

27. Padua, D. A., Marshall, S. W., Boling, M. C., Thigpen, C. A., Garrett, W. E., Jr. & Beutler, A. I. (2009). The Landing Error Scoring System (LESS) is a valid and reliable clinical assessment tool of jump-landing biomechanics: The JUMP-ACL study. American Journal of Sports Medicine, 37(10), 1996-2002.

Google Scholar

28. Quatman, C. E., Kiapour, A. M., Demetropoulos, C. K., Kiapour, A., Wordeman, S. C., Levine, J. W., Goel, V. K. & Hewett, T. E. (2014). Preferential loading of the ACL compared with the MCL during landing: A novel in sim approach yields the multiplanar mechanism of dynamic valgus during ACL injuries. American Journal of Sports Medicine, 42(1), 177-186.

Google Scholar

29. Rajagopal, A., Dembia, C. L., DeMers, M. S., Delp, D. D., Hicks, J. L. & Delp, S. L. (2016). Full-body musculoskeletal model for muscle-driven simulation of human gait. IEEE Trans- actions on Biomedical Engineering, 63(10), 2068-2079.

Google Scholar

30. Rosen, A. B., Needle, A. R. & Ko, J. (2019). Ability of functional performance tests to identify individuals with chronic ankle instability: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine, 29(6), 509-522. https://doi.org/ 10.1097/JSM.0000000000000535

Google Scholar

31. Siupsinskas, L., Garbenyte-Apolinskiene, T., Salatkaite, S., Gudas, R. & Trumpickas, V. (2019). Association of pre-season musculoskeletal screening and functional testing with sports injuries in elite female basketball players. Scientific Reports, 9(1), 9286. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-45773-0

Google Scholar

32. Tamura, A., Akasaka, K., Otsudo, T., Shiozawa, J., Toda, Y. & Yamada, K. (2017). Dynamic knee valgus alignment in- fluences impact attenuation in the lower extremity during the deceleration phase of a single-leg landing. PloS One, 12(6), e0179810. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone. 0179810

Google Scholar

33. Taylor, J. B., Ford, K. R., Schmitz, R. J., Ross, S. E., Ackerman, T. A. & Shultz, S. J. (2017). Biomechanical differences of multidirectional jump landings among female basketball and soccer players. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 31(11), 3034-3045. https://doi.org/Doi10.1519/ Jsc.0000000000001785

Google Scholar

34. Turner, J. A., Chaaban, C. R. & Padua, D. A. (2024). Validation of OpenCap: A low-cost markerless motion capture system for lower-extremity kinematics during return-to-sport tasks. Journal of Biomechanics, 171, 112200. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2024.112200

Google Scholar

35. Uhlrich, S. D., Falisse, A., Kidzinski, L., Muccini, J., Ko, M., Chaudhari, A. S., Hicks, J. L. & Delp, S. L. (2023). OpenCap: Human movement dynamics from smartphone videos. PLOS Computational Biology, 19(10), e1011462. https:// doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1011462

Google Scholar

36. Verheul, J., Robinson, M. A. & Burton, S. (2024). Jumping towards field-based ground reaction force estimation and assessment with OpenCap. Journal of Biomechanics, 166, 112044. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiomech.2024.112044

Google Scholar

37. Zwolski, C., Schmitt, L. C., Thomas, S., Hewett, T. E. & Paterno, M. V. (2016). The utility of limb symmetry indices in return-to-sport assessment in patients with bilateral anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. American Journal of Sports Medicine, 44(8), 2030-2038.

Google Scholar